⭐

In recent years I’ve developed an increasing interest in conspiracies and cults, most especially in what sorts of people are the most likely to believe in them and what exactly drives them to do so. You can’t really delve into this subject without also touching upon folklore and cryptozoology, and my fondness for horror and relative open-mindedness about such things means I wouldn’t want to avoid them. As a result, I was very intrigued by John O’Connor’s The Secret History of Bigfoot, a book which purported to examine both the myth itself and its most ardent believers, but which unfortunately turned out to feel more and more like the author’s philosophical ramblings as it went on.

It begins well enough, as O’Connor regales the reader with his exploits trekking along the Appalachian Trail, in search of the elusive creature and those who claim to have seen it. He writes in a fun, conversational style, laced with beautiful descriptions of the natural world around him and frequent diversions into David Sedaris-like humor. The first several chapters carry on in much the same enjoyable way. Some psychological theorizing is peppered throughout these early sections and it offers some keen insights into the parts of modern life that might make people susceptible to believe so deeply in something so seemingly impossible.

About halfway through the book though, the psychoanalysis and philosophizing almost completely take over, with mentions of Bigfoot becoming rarer and rarer. The author makes several good points, most especially as to how the whole thing relates to our planet’s dwindling natural resources, and remains pleasant enough to read, but as he gets further and further from the stated subject of the book, one questions what it’s even about. The surprisingly high number of liberal talking points is also likely to put off some readers entirely, and usually feels completely out of place.

In the end, O’Connor brings it back around and attempts to draw some conclusions from his experiences. He refreshingly avoids coming down for or against Bigfoot’s existence, though is clearly skeptical, and expresses at least some respect towards the different people he encountered along the way (I suspect at least a few are unlikely to speak to him again after reading this however). He also manages to leave the reader with a lingering wistfulness for the amount of the natural world that has already been lost forever. It is frequently posited herein that one of the reasons we want so badly to believe in Bigfoot and his ilk is that it allows us to believe that there is still something of mystery out there, despite mankind’s never-ending encroachment into the wilderness. It feels like there is something to the theory. As author and naturalist Peter Matthiessen is quoted saying in the book, “I think it’s going to be a very dull world when there’s no more mystery at all.” ★★★

Feb 9, 2024

Related Recs

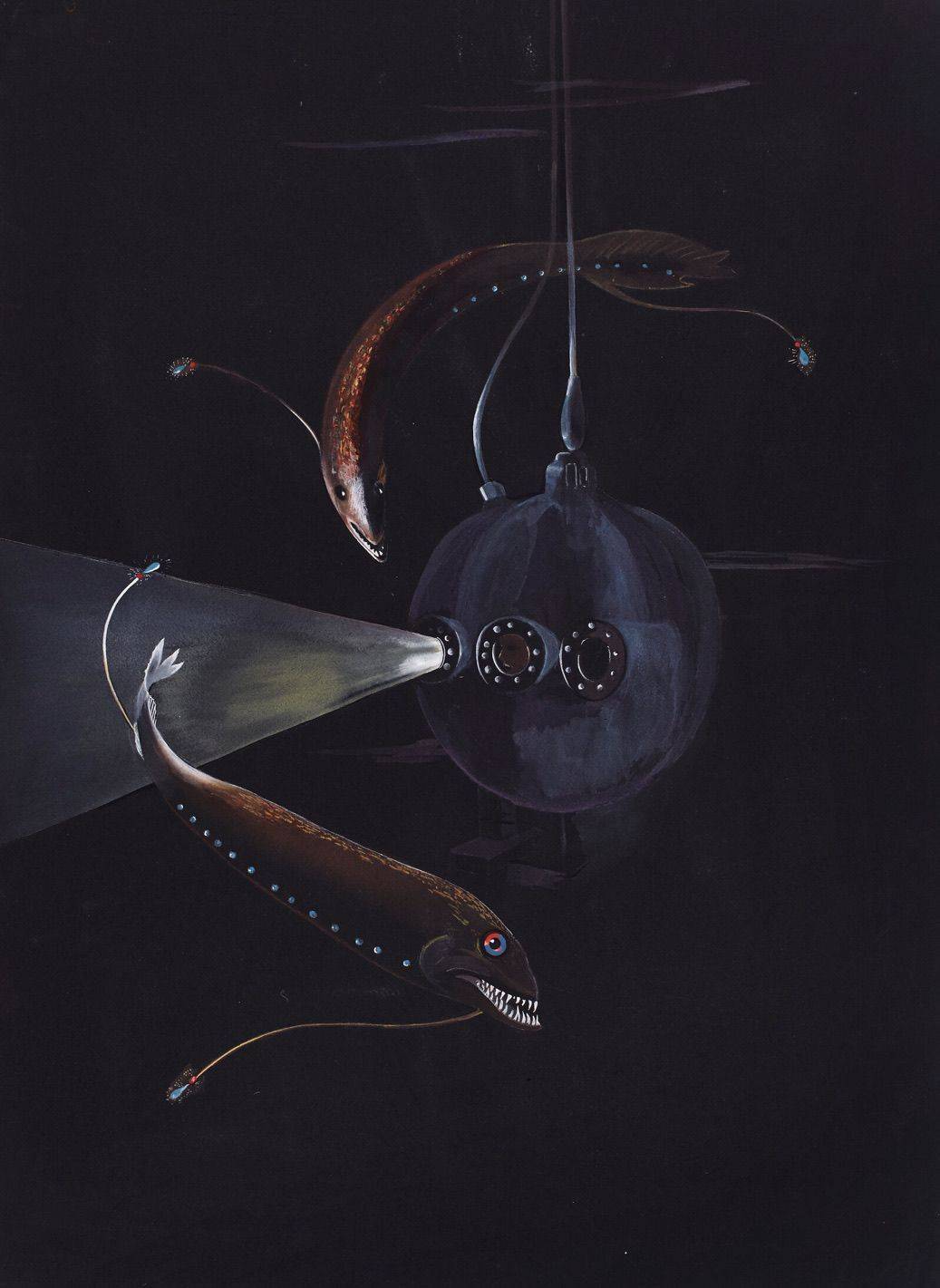

One of the most memorable and fascinating books I have read in a while. This is about, among other things, early 20th century explorer and scientist William Beebe’s adventures and exploits in exploring the unseen deep ocean and witnessing all its strange life forms in a bathysphere, as well as stories about his contemporaries/friends of the era and general musings on the nature of exploration. Chapters are not always linear and include his logbook entries and illustrations, they’re no more than 2-3 pages at a time, capturing vivid vignettes and creating an almost dream like type of prose, much like the wonder and awe Beebe must have experienced seeing all of this himself- it’s far from a dry scientific account- the author Brad Fox has truly done something special here. Really cannot do it justice so check it out yourself to see.

Sep 11, 2024

🦋

This book was recommended to me by the discerning Chris Gabriel who makes videos under the name Meme Analysis. It’s a pulpy “nonfiction” account of Keel’s investigation into eyewitness reports of the mothman in the late 1960s. Stories of the unexplained (ghosts, visions, conspiracies) are best when they play on the stranger-than-fiction truths of real life. Whether or not the events in this book actually happened, Keel’s stories are so unique and eerie in their specificity that the truth they suggest is undeniable: “If there is a universal mind, must it be sane?” Must it???

Apr 4, 2024

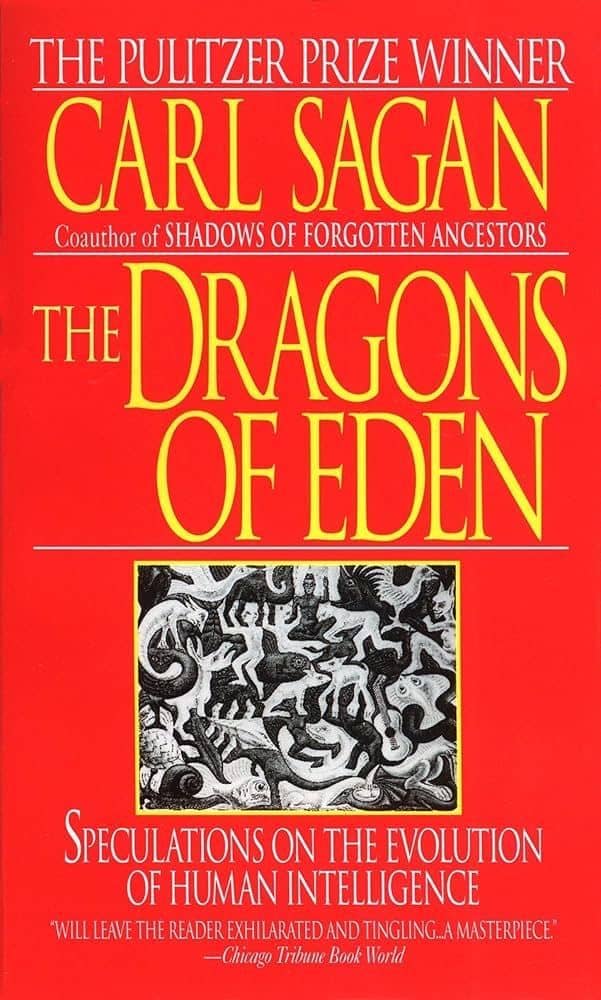

Really interesting interdisciplinary speculative science book about the development of human intelligence, written in a lovely prosaic voice that makes it accessible to and engaging for anyone. There have been significant scientific advancements that add nuance and complexity to some of the ideas he discusses but it’s still useful as a conceptual framework for understanding and it’s interesting to see the conclusions he was able to draw with his brilliant mind based off of the limited information that was available at the time. He raises a lot of thought provoking questions—its greatest value is as a philosophical text—and I think it’s still more than worth your time to read today.

“As a consequence of the enormous social and technological changes of the last few centuries, the world is not working well. We do not live in traditional and static societies. But our government, in resisting change, act as if we did. Unless we destroy ourselves utterly, the future belongs to those societies that, while not ignoring the reptilian and mammalian parts of our being, enable the characteristically human components of our nature to flourish; to those societies that encourage diversity rather than conformity; to those societies willing to invest resources in a variety of social, political, economic and cultural experiments, and prepared to sacrifice short-term advantage for long-term benefit; to those societies that treat new ideas as delicate, fragile and immensely valuable pathways to the future.”

Jan 14, 2025

Top Recs from @seanf

Tried and true formulas work for a reason, and there’s nothing inherently wrong with hewing to them as long as the result is still good, but it’s always exciting for me to watch a movie and feel like I’m seeing something genuinely new and different. Greek filmmaker Yorgos Lanthimos (The Favourite, The Lobster) has so far proven very adept at achieving that, even when building stories around pre-existing works, as he does here. Working off a script by Tony McNamara (The Great, The Favourite as well) based on Alasdair Gray’s 1992 novel which was itself heavily inspired by Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, Lanthimos has crafted an epic tale of a woman discovering who she is when freed from the restrictive, largely male-imposed norms of the society around her.

Bella Baxter (Emma Stone) is effectively the creation of Dr. Godwin “God” Baxter (Willem Dafoe), a disfigured but respected surgeon in a strange, steampunk-inspired version of old London, whose house is filled with various creatures he’s spliced together. When he discovers the body of a recently deceased woman in the river, he inserts the brain of her unborn child into her head and so brings both back to life. Bella’s brain is not ready to inhabit an adult’s body however, and so she has difficulty walking let alone communicating. For some reason though, the procedure causes her brain to begin developing at a highly increased rate, and she starts picking up language and other more complicated concepts very quickly.

Godwin is impressed by this result and enlists one of his students, Max McCandles (Ramy Youssef) to monitor her and note her progress. Over time, Bella begins to chafe against the strict boundaries placed upon her by her “father” Godwin, demanding to be allowed out into the world, while also beginning to form a deep bond with the sweetly sympathetic (but still meekly complicit) Max. When she encounters the rakish lawyer Duncan Wedderburn (Mark Ruffalo) she is instantly taken by his promise of escape, but not fully understanding the concept of a secret, she blurts out her plans to Godwin. Surprisingly, he realizes that her need to see more of the world is not unreasonable and so he reluctantly assents to let her go. Thus begins Bella’s odyssey around the Mediterranean, in which she experiences much of the good and the bad in the world while learning to take control of her womanhood.

Stone is magnificent as Bella, completely inhabiting each phase of her growth; from the temper tantrums of a child, to the passions of a young woman discovering her body, to the cool, calm demeanor of an intelligent lady who knows exactly what she wants in life. Ruffalo’s strange, unplaceable accent from All the Light We Cannot See seems to have returned here, though it works far better with the overall unusual tone, and he nails the petulant befuddlement of a man realizing that he can’t handle himself when a woman treats him the same way he has long treated women. Dafoe is excellent as always and Youssef charms in his role, though this is truly Stone’s movie through and through.

The world that Lanthimos has dreamt up for our characters to inhabit is striking and captured beautifully by cinematographer Robbie Ryan (C’mon C’mon, The Favourite again). Likewise, the off kilter yet beautiful score by Jerskin Fendrix is a perfect complement to the story. McNamara’s script has stripped the original book to its most essential pieces and is rife with raunchy, absurdist humor, but it’s the film’s deeper themes that make it truly special.

Bella’s life is initially completely controlled by the men around her. Even if they are sometimes well-meaning in their intentions, they are still forcing their ideas of who she should be allowed to become upon her. It is only when she is granted her freedom that she is able to grow into her true self and begin to thrive. She learns several of her own lessons along the way, with the movie even going so far as to spell out one of its main points for her and us, when brothel-owner Swiney tells Bella, “We must experience everything. Not just the good, but degradation, horror, sadness. This makes us whole Bella, makes us people of substance. Not flighty, untouched children. Then we can know the world. And when we know the world, the world is ours.” Imaginative, funny, charming, filthy, wise, engaging, weird, and wonderful, Poor Things is Lanthimos’ best work yet, and a modern adult fairy tale worth treasuring. ★★★★★

RATED R FOR STRONG AND PERVASIVE SEXUAL CONTENT, GRAPHIC NUDITY, DISTURBING MATERIAL, GORE, AND LANGUAGE.

Feb 29, 2024

Mar 2, 2024

When Terry Hayes’ debut novel I Am Pilgrim burst onto the scene a decade ago, it seemed to announce the arrival of a major new talent in the thriller scene. I absolutely loved the book and was very excited to see what he would come up with when his next title, The Year of the Locust, was announced for release in 2016. Unfortunately, the year came and went without the book, as did several more, making it seem as if it might never be published. Lo and behold, 8 years later, it’s finally here, and as it turns out it was worth the wait.

The book is written from the perspective of Kane, a Denied Access Area spy for the CIA. His job is to get into the places that Americans aren’t supposed to go and get back out again without being caught, and he is one of the best in the business. When we meet him, he is being sent to the borderlands of Pakistan, Afghanistan, and Iran to try to gather information about an increasingly powerful terrorist group known as the Army of the Pure. Intel has suggested that they are planning a major attack that will endanger countless people around the world and so it is imperative that he can learn more about the organization so they can be stopped before it is too late. Of course, with these kinds of missions there is a lot that can go wrong, and Kane finds himself in some very bad scenarios, with only his wits and training to help him survive.

Written in a conversational tone and short, punchy chapters (some barely a page long), the novel’s roughly 800 pages fly by. Kane is an easy character to like, and the book can sometimes feel like he’s a friend telling you a story. That story happens to be relentlessly suspenseful though, filled with some of the tensest moments of any book I’ve read in years. I would frequently find myself feeling a palpable sense of relief at the conclusion of a mission, having been every bit as invested in its outcome as the characters involved. Speaking of which, while Kane is the star, the other characters are equally enjoyable to spend time with and help to further draw in the reader.

Hayes has clearly done his homework when it comes to spycraft, providing fascinating insights into that world throughout. Everything is so convincing that it can be hard to tell what’s in actual use or the author’s invention, and while it is all thoroughly explained it never gets boring.

The finale takes the story into some truly surprising territory that readers will never see coming and which raises the stakes to truly astronomical levels. Parts of it require some suspension of disbelief, but Hayes pulls off the shift so well that most readers won’t have any problem going along for the ride. 10 years between books is a long time to wait, but when the result is this thrilling, inventive, and even surprisingly emotional it seems like it paid off. Though, it’s still very early into the year, I’d be surprised if I read a more entertaining book than this one in 2024. ★★★★★

Feb 5, 2024