🎣

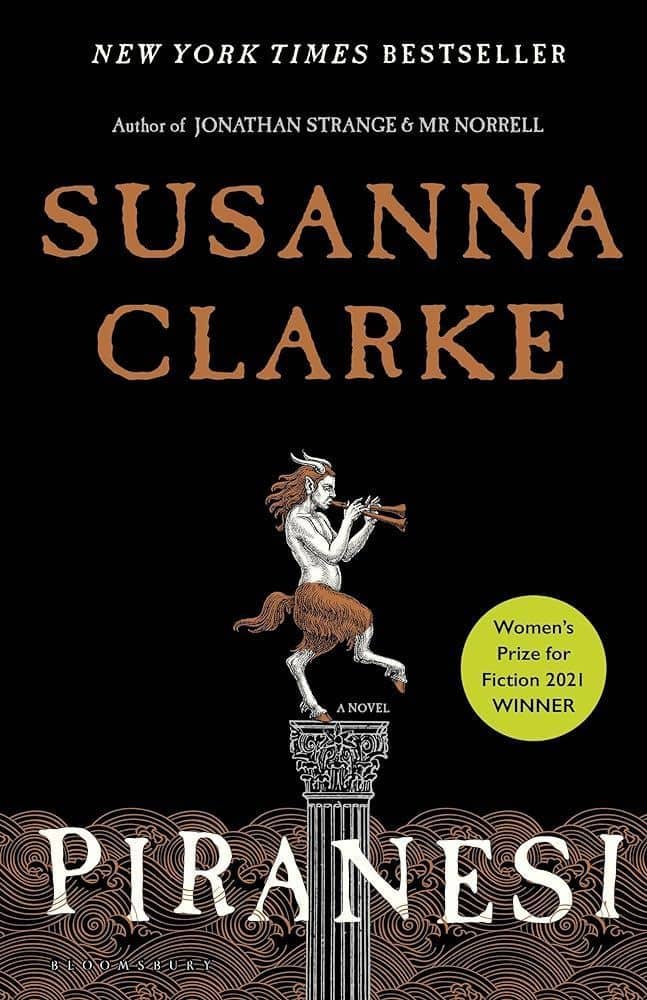

Very compelling quick read with some of the best environmental storytelling out there. Scratched my modern fantasy itch hard

Feb 28, 2024

Related Recs

📕

This is a modern sci-fi book that, unlike some of my previous sci fi recommendations, spends a bit more time on character than the science behind the story. This works in it's favor, giving you some really great characters you care a lot about, but it doesn’t sacrifice much on the sci-fi side. It’s still a fun mind-bending journey.

Oct 15, 2020

In recent years I’ve developed an increasing interest in conspiracies and cults, most especially in what sorts of people are the most likely to believe in them and what exactly drives them to do so. You can’t really delve into this subject without also touching upon folklore and cryptozoology, and my fondness for horror and relative open-mindedness about such things means I wouldn’t want to avoid them. As a result, I was very intrigued by John O’Connor’s The Secret History of Bigfoot, a book which purported to examine both the myth itself and its most ardent believers, but which unfortunately turned out to feel more and more like the author’s philosophical ramblings as it went on.

It begins well enough, as O’Connor regales the reader with his exploits trekking along the Appalachian Trail, in search of the elusive creature and those who claim to have seen it. He writes in a fun, conversational style, laced with beautiful descriptions of the natural world around him and frequent diversions into David Sedaris-like humor. The first several chapters carry on in much the same enjoyable way. Some psychological theorizing is peppered throughout these early sections and it offers some keen insights into the parts of modern life that might make people susceptible to believe so deeply in something so seemingly impossible.

About halfway through the book though, the psychoanalysis and philosophizing almost completely take over, with mentions of Bigfoot becoming rarer and rarer. The author makes several good points, most especially as to how the whole thing relates to our planet’s dwindling natural resources, and remains pleasant enough to read, but as he gets further and further from the stated subject of the book, one questions what it’s even about. The surprisingly high number of liberal talking points is also likely to put off some readers entirely, and usually feels completely out of place.

In the end, O’Connor brings it back around and attempts to draw some conclusions from his experiences. He refreshingly avoids coming down for or against Bigfoot’s existence, though is clearly skeptical, and expresses at least some respect towards the different people he encountered along the way (I suspect at least a few are unlikely to speak to him again after reading this however). He also manages to leave the reader with a lingering wistfulness for the amount of the natural world that has already been lost forever. It is frequently posited herein that one of the reasons we want so badly to believe in Bigfoot and his ilk is that it allows us to believe that there is still something of mystery out there, despite mankind’s never-ending encroachment into the wilderness. It feels like there is something to the theory. As author and naturalist Peter Matthiessen is quoted saying in the book, “I think it’s going to be a very dull world when there’s no more mystery at all.” ★★★

Feb 9, 2024

Top Recs from @willmoon

🚭

I'm at a point in my life where many of my peers will say that they intend to quit someday, but just not yet. Besides the most obvious reasons for giving up nicotine and tobacco, here are some of the short-term benefits I've found since my hiatus.

- Exercising self-control

- better lung capacity

- getting rid of the smell that sticks to your clothes

- no nic-shits

- less nausea

- better appetite

- far less frequent cravings

In short, you don't have to give up going outdoors to chat with your smoking friends, but you can find autonomy in choosing your battles wisely—Or not, its really up to you.

Jan 5, 2025

Jan 15, 2025

🦕

dont you dare say you’re too old for it

Mar 6, 2024